Classification of osteoporosis

Postmenopausal osteoporosis and senile osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is often divided into so-called postmenopausal osteoporosis and so-called senile osteoporosis or senile osteoporosis. According to this classification, postmenopausal osteoporosis affects women who have passed the menopause up to the age of 65, afterwards it is referred to as old age osteoporosis. However, this subdivision is very arbitrary and ultimately not justified by any direct logical or causal relationships. So it is hard to see why the diagnosis of “postmenopausal osteoporosis” should suddenly be changed to the diagnosis of “geriatric osteoporosis” six months later at the age of 65 for a woman at the age of 64 ½ years, for example. Therefore we do not use this classification. After all, the cause of osteoporosis is always a pathologically increased bone loss, whereby the causes for this increased bone loss are again very diverse. Depending on the height of the originally reached peak bone mass and depending on the rate of bone loss, it then of course also takes a different amount of time until the limit to osteopenia and later to osteoporosis is reached or undershot.

The development of osteoporosis is always a long-lasting process that is promoted by numerous causes and risk factors, whereby the estrogen deficiency in women after menopause is just one cause among many (and actually the only logical cause, which is called “postmenopausal osteoporosis “Could logically justify). The causes and risk factors that ultimately lead to osteoporosis or not are the same for “postmenopausal osteoporosis” and “old age osteoporosis”. It is therefore hard to see why this classification should be used to make an arbitrary distinction between postmenopausal and senile osteoporosis, depending only on age! In addition, the so-called old age osteoporosis after the age of 65 is always also a post-menopausal osteoporosis in women (menopause usually occurs around the age of 50, so that every woman after the age of 65 is of course always in postmenopausal stage of life).

Type I osteoporosis and Type II osteoporosis

The distinction between the so-called type I osteoporosis and the so-called type II osteoporosis seems more appropriate here. This differentiation relates to the two different bone components: the “trabecular bone” and the “cortical bone” or “compact bone”, which are explained in more detail in the main point “Osteoporosis – Causes”. Since the trabecular bone (trabecular bone) has a much faster metabolism (remodeling) than the much more sluggish compact bone, osteoporotic bone resorption usually affects the trabecular bone much more strongly than the compact bone. Therefore, the bone density in type I osteoporosis is initially only reduced in the trabecular bone, while the compact bone can still have a completely normal bone density. Only after prolonged, pathologically increased bone resorption is the compact bone increasingly affected by this breakdown, so that finally the bone density in both bone components is reduced. In this respect, postmenopausal osteoporosis roughly corresponds to type I osteoporosis and old age osteoporosis to type II osteoporosis. This differentiation seems to make more sense, as it is more oriented towards so-called pathophysiological criteria, i.e. metabolic-causal conditions.

However, this differentiation for the diagnosis by means of bone density measurement requires a method that can also detect these two bone components separately (selectively), which in turn is only possible with computed tomographic methods (see also sub-item “Diagnosis – Bone Density Measurement) and not, for example, with ultrasound or the DXA method. The DXA method, which is still often referred to as the “gold standard”, has the advantage that measurements can be made on the bones on which the most serious fractures occur, i.e. the spine and the femoral neck; However, it cannot differentiate between the two bone building blocks and thus also not type I osteoporosis from type II osteoporosis. This disadvantage is somewhat offset by the fact that the vertebral body consists mainly of trabecular bones and the femoral neck consists mainly of compact bones, but the trabecular and compact bone densities can be measured directly with computer tomographic bone density measurements. And since osteoporosis is a systemic bone disease and the osteoporotic bone degradation affects the trabecular and compact bones in the entire skeleton to a greater or lesser extent, the measurement on the spine or the femoral neck does not necessarily have such a weighty advantage that the designation “gold standard” justifies.

High turnover and low turnover osteoporosis (fast and slow loser concept)

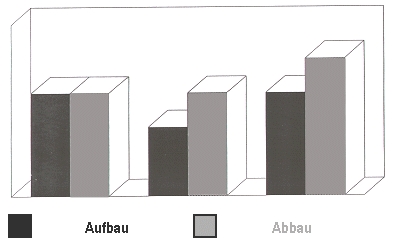

In our opinion, the most convincing classification of osteoporosis is the so-called high-turnover osteoporosis with rapid bone loss (fast-loser situation) and a so-called low-turnover osteoporosis (slow-loser situation) low rate of bone loss. This classification is based on the speed of the underlying bone degradation rate (dynamics) in the context of so-called remodeling. If bone formation and bone resorption are in balance (Fig. Below left), the remodeling is in balance, i.e. exactly as much bone is built up as was previously broken down. If the rate of bone loss is higher than normal and exceeds the rate of bone formation (Fig. Below right) or if the rate of bone regeneration is reduced (Fig. Below center), the sum of both situations always results in increased bone mass loss. If both factors come together (ie a high rate of breakdown and a low rate of breakdown), the rate of bone breakdown is increased far beyond the normal level and we are faced with a typical “fast-loser situation”.

However, this has decisive consequences for the therapy, because in the case of an increased bone loss rate we have to try to slow down this increased bone loss or even better stop it completely, whereas in the case of a balanced metabolic situation we could try to increase the bone formation rate. Accordingly, we differentiate between drugs that either slow down an increased rate of bone breakdown (“antiresorptives”) and drugs that stimulate the rate of bone breakdown. This differentiation of osteoporosis makes sense both with regard to the underlying pathophysiology (metabolic-causal) and with regard to the treatment strategies that result from it (see subsection “Fast and Slow Loser Concept” under bone density measurement in the subsection Diagnosis). We consider this concept to be much more practical, both in terms of the indication (necessity) of a therapy (even if the bone density is not yet significantly reduced) and the choice of therapy (inhibiting bone loss or stimulating bone formation). If the rate of the underlying bone loss is fast, the main thing we need to do is to brake this increased rate of bone loss (just as you put the handbrake on a car parked on a sloping street). If the rate of bone loss is not increased, but the bone density is already significantly reduced (stable bone turnover ratio, albeit at a low level), we should primarily try to increase the rate of bone formation (comparable to the situation in a car when the battery is empty and we are the car need to push to start).

However, this has decisive consequences for the therapy, because in the case of an increased bone loss rate we have to try to slow down this increased bone loss or even better stop it completely, whereas in the case of a balanced metabolic situation we could try to increase the bone formation rate. Accordingly, we differentiate between drugs that either slow down an increased rate of bone breakdown (“antiresorptives”) and drugs that stimulate the rate of bone breakdown. This differentiation of osteoporosis makes sense both with regard to the underlying pathophysiology (metabolic-causal) and with regard to the treatment strategies that result from it (see subsection “Fast and Slow Loser Concept” under bone density measurement in the subsection Diagnosis). We consider this concept to be much more practical, both in terms of the indication (necessity) of a therapy (even if the bone density is not yet significantly reduced) and the choice of therapy (inhibiting bone loss or stimulating bone formation). If the rate of the underlying bone loss is fast, the main thing we need to do is to brake this increased rate of bone loss (just as you put the handbrake on a car parked on a sloping street). If the rate of bone loss is not increased, but the bone density is already significantly reduced (stable bone turnover ratio, albeit at a low level), we should primarily try to increase the rate of bone formation (comparable to the situation in a car when the battery is empty and we are the car need to push to start).

Manifest and preclinical osteoporosis

A very decisive prerequisite for whether an osteoporosis needs treatment or not is the fact whether it is a so-called manifest osteoporosis or a so-called preclinical osteoporosis. This differentiation is based primarily on the possibly already existing consequences of osteoporosis, the most serious of which is the osteoporotic bone fracture and, in particular, the vertebral fracture or the femoral neck fracture. If osteoporosis is only defined on the basis of reduced bone density (WHO definition) without osteoporotic bone fractures having already occurred, we speak of preclinical osteoporosis, a type of “latent” osteoporosis without any consequences that have already occurred. This low bone density can be the consequence of a summit bone mass that was originally below average (with a normal bone structure) as well as a result of previous bone loss (with an increased rate of bone loss).

The diagnosis of preclinical osteoporosis therefore primarily refers to an increased risk of bone fractures due to reduced bone density. Whether or not preclinical osteoporosis requires treatment depends primarily on whether the rate of bone loss is increased or not. Whether the rate of bone loss is increased can be determined either with a subsequent control measurement of the bone density (then the bone density measured in the second bone density measurement is significantly lower than in the first measurement) or by means of a laboratory test (if the so-called bone loss markers are increased). In the case of high turnover osteoporosis with an increased rate of bone breakdown, more bone breakdown products are produced, which can be measured in the blood or urine.

The accelerated degradation of bone does not “dissolve into air”, but is “broken down” into smaller building blocks, which are transported in the blood (e.g. beta crosslaps) and excreted with the urine (deoxipyridinoline). Accordingly, these degradation products, which occur more frequently, can also be detected in the blood and urine (here, however, certain conditions are necessary with regard to the point in time at which the blood is drawn or the urine collection and with regard to the further processing of the samples, which must be precisely observed in order to obtain accurate results). The diagnosis of manifest osteoporosis describes a clinical picture which has already led to osteoporotic bone fractures – regardless of the bone density measured in each case. So if osteoporotic bone fractures – especially vertebral fractures – have already occurred, this situation is definitely in need of treatment!

Primary and Secondary Osteoporosis

The division into primary and secondary osteoporosis is important for therapy for other reasons. Often the exact cause of the osteoporosis cannot be determined – in this case we speak of primary osteoporosis. Primarily in medicine it is mostly an interesting-sounding paraphrase for the fact that we do not know the actual causes. Since osteoporosis is usually a so-called multifactorial disease (i.e. there are numerous causes that are often mutually reinforcing), the medical history (personal medical history) and the presence of risk factors play a central role. Sometimes, however, other underlying diseases (chronic intestinal disease, hyperthyroidism, etc.) or the intake of certain medications (cortisone, marrowam to thin the blood, neuroleptics – antispasmodic drugs – or excessively high doses of thyroid hormones) are the actual triggering cause of the pathologically increased bone loss.

In these cases we speak of secondary (based on other causes) osteoporosis. Here, of course, the treatment of the underlying disease or the reduction of appropriate medication (if possible!) Is in the foreground, as this even enables a causal (causal) treatment. If the underlying disease (e.g. chronic intestinal disease such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) cannot be cured or a reduction or discontinuation of the respective medication (e.g. cortisone for rheumatism or asthma) is not possible, the osteoporosis must be symptomatic as well (as with primary osteoporosis) be treated.